Diagnosing and Treating Eating Disorders: What All Clinicians Need to Know

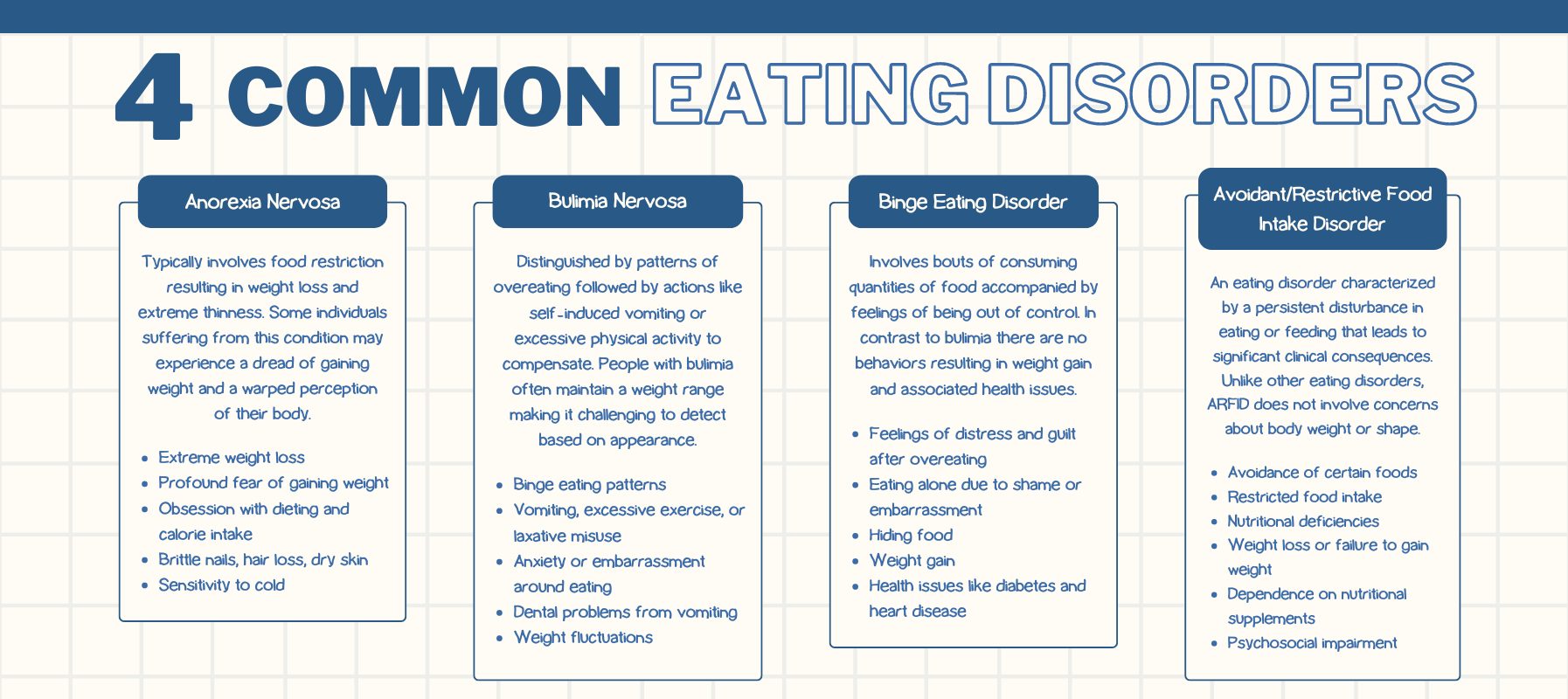

Diagnosing eating disorders is often tricky and treating eating disorders can be even trickier. Although eating disorders are often times fraught with complexity — including comorbid mental health diagnoses and potential health risk, it is important for mental health clinicians to better understand how to diagnose and treat an eating disorder and when to make an eating disorder treatment referral. Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge Eating Disorder (BED), and Avoidant/Resistant Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) vary in terms of presentation and therefore come with their own unique challenges that require specialized knowledge to help aid in the diagnosis process.

Even if you don’t believe you can work with eating disorders or don’t want to as a mental health clinician, we all have a responsibility to understand these disorders and recognize their warning signs and symptoms. We all have a relationship with food and our bodies, therefore eating disorders are a universal issue in mental health care that every client will have to face.

Free Download: The Mental Health Clinician's Guide to Diagnosing and Treating Eating Disorders

Diagnosing Eating Disorders

When identifying an eating disorder, it is important to consider what we understand an eating disorder to be. Although the DSM-5 restricts Anorexia Nervosa to a BMI below 17.5, it does not exclude people above a 17.5 BMI from displaying eating disorder symptoms. Therefore, it is important to identify an eating disorder from a weight inclusive approach, which means you consider the behaviors, physical symptoms, and psychological and cognitive concerns as indicators versus a person’s weight. This takes into consideration that people in larger bodies can also suffer from a restrictive eating disorder and will prevent folks from slipping through the cracks.

Eating disorders go beyond food; they are mental health conditions that impact both physical and emotional well being. These disorders can dominate a client's life making everyday tasks and social interactions seem overwhelming.

Eating disorders also go beyond eating patterns. They are closely linked to a client's well being and self perception. Individuals dealing with these issues often struggle with feelings of inadequacy and a fear of gaining weight.

Mental health problems like anxiety and depression often play a role in the development of eating disorders. Pressures from society to maintain a body image can intensify these emotions driving people towards behaviors as they try to conform to unrealistic standards. It's important to note that eating disorders affect everyone; although young women are commonly highlighted individuals of any age, gender or background can be impacted.

Early detection is crucial. The sooner signs of an eating disorder are addressed, the better the chances for recovery. If left untreated these conditions can lead to health complications, both mentally and physically.

Behavioral Symptoms of Eating Disorders

An important part of an eating disorder is behaviors and a drive to do them. Although you see a client for just a short period of time during their week, asking questions about their eating patterns and their perception of self may illuminate behaviors that could be more serious and a sign that your client is upholding an eating disorder. Below are things to consider in session:

- Dieting: If your client is describing going on a diet or talks about dieting often, ask them more about how the dieting plays a role in their life. Important questions to ask would be around how restrictive their diet is. Intensive calorie counting or severely cutting out certain food groups could be a sign that their diet is actually restrictive behavior.

- Nighttime Snacking / Binging Behaviors: Listen closely if your client describes feeling “shame” or “guilt” around eating large amounts of food, especially at night. Inquiring about when the consumption of large amounts of food happens may point to a struggle with binge eating in order to cope and help with emotional regulation. Also consider asking the client “what does a large amount of food look like to you?” The answer to this question may provide you with more insight and a tangible idea of how much they are eating.

- Social Withdrawal or Avoidance of Activities: When we see social withdrawal in a client, it can mean a lot of things and may not be exclusively linked to an eating disorder. Where social withdrawal matters in eating disorders is when clients avoid activities that may involve eating or activities where their body is going to be heavily perceived (swimming, sports, going out to eat and shopping — to name a few). It’s important to ask further Socratic questions to understand how the client’s thoughts may be linked to these behaviors.

Physical Symptoms of Eating Disorders

Although the physical symptoms of an eating disorder may be harder to notice and even harder for us to bring up in session, physical symptoms may also aid us in better identifying an eating disorder and therefore, asking our clients questions that can lead to a proper diagnosis.

- Weight Loss / Weight Fluctuation: It may be hard to notice when a client loses weight but if the restrictive behaviors have been active for a while, you will begin to see a rapid change in how your client looks. If you notice a weight fluctuation or drastic weight loss, it would be worth asking your client about their relationship to their body and to eating if you have not broached the subject already. Asking these questions can at times seem inorganic but continuing to frame the conversation around eating and bodies as a universal experience will help normalize these questions for the client.

- Cycle Changes or Losses of Periods: Depending on the sex of your client and depending on the type and severity of the disorder — clients who heavily restrict may have a drastic change in their menstrual cycle or a complete loss of it. Although this might not be something that naturally comes up in session, being aware that this is a symptom may clue you in if your clients speaks about it in session naturally as a concern or problem for them.

- Fainting: Like the other physical symptoms listed above, fainting may not come up for the client in session. Be aware of how the client is in session, if you begin to notice a client losing their train of thought or appear exceptionally tired, a restrictive eating pattern can cause fainting and slower cognitive functioning, making staying present and focused in conversation harder as well.

- Dizziness or Fatigue: Complaints of feeling frequent dizziness are common among individuals with eating disorders due to malnutrition and insufficient caloric intake. Nutritional deficiencies can also lead to fatigue and an overall sense of unwellness.

- Brittle Hair and Nails: Other physical signs of malnutrition include brittle hair and nails.

- Gastrointestinal Issues: Irregular eating patterns can result in constipation or bloating.

Psychological Symptoms of Eating Disorders

Where mental health clinicians must be acutely aware of eating disorder symptoms is through the psychological and cognitive manifestations. It’s important to note that psychological and cognitive symptoms are the symptoms we will hear about the most.

- Preoccupation with Food / Weight / Body Shape: If you notice your client discussing food, weight, or body shape more than normal — it is important to inquire how much these thoughts come up for them around their preoccupation and how much it affects their daily life. Preoccupation with food, weight, or body shape can lead to behaviors, so it’s important to inquire thoroughly about their level of distress with these thoughts.

- Body Dissatisfaction / Distorted Body Image: Clients who are struggling with an eating disorder may talk at length about their dissatisfaction with their body or describe their body negatively. With both restrictive and binge related eating disorders, emotions such as guilt, shame, and disgust come up often as they think about their body shape. Notice when clients are viewing themselves much larger than they are and expressing disapproval. Also, stay tuned in if your client compares their body to someone else, if your client is expressing desire for another person’s body shape or a “dream body” you may need to do more investigation into if your client is doing something to achieve that “dream body”.

- Low Self-Esteem, Depression, Anxiety, Irritability: Along with body dissatisfaction and distorted body image, clients may display low self-esteem about themselves due to their body and judge their worth and value based on what their body looks like. This in turn can manifest into depression, anxiety, and irritability. It is important to note that these symptoms are rooted in their perception of worthiness based on weight and shape.

- Rigid Thinking: If a client discusses food with you in session, listen closely to how they describe and categorize food. The use of rigid words like “good” and “bad” when it comes to food may point to restrictive behaviors in fear of consuming “bad” foods. Often in restrictive eating disorders, folks will identify “safe” foods which the individual allows themselves to eat. This can lead to cutting out major sources of nutrients and reducing calories to a dangerous amount. Additionally, inquire more when clients discuss body weight in rigid terms. If a client describes only small-bodied people as healthy, ask the client why body weight is indicative of health, this could lead to understanding that your client sees health as a paradigm that relies on weight.

Factors Contributing to Eating Disorder Development

Several factors contribute to the emergence of eating disorders, including genetic predispositions and environmental influences. Having a family history of eating disorders increases the likelihood of developing one. Genetics play a significant role in susceptibility.

Past trauma or high-stress events often coincide with the onset of eating disorders. Emotional distress from traumatic experiences can lead to unhealthy coping mechanisms.

The pressure to fit the societal standards of beauty and thinness can be especially daunting for young individuals, who may feel compelled to conform. Factors such as perfectionism and anxiety can further elevate the risk. Identifying these risk factors is crucial to early intervention, improved health outcomes, and faster recovery.

Review a Sample Eating Disorder Chart created in ICANotes

Treating Eating Disorders

When it comes to treating an eating disorder, your choices of treatment depend on severity, type of presentation, and equity. Usually a combination of psychotherapy, medical care and monitoring, nutritional counseling, and medications are used to help treat an eating disorder. If an eating disorder can be treated in outpatient psychotherapy — meaning the client’s symptoms are not yet severe enough to require a higher level of care, it’s important to make sure the client also has a nutritionist and psychiatrist they are seeing in conjunction with your care. This creates a comprehensive treatment plan where medical concerns and psychiatric concerns are being closely monitored.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-E): An adaption of CBT for eating disorders, called CBT-E is often used in outpatient settings and in some higher levels of care to help identify patterns of thoughts, emotions and behaviors that influence our eating behaviors and over-evaluation of weight and shape. Where CBT-E is different from CBT is that it follows four distinct stages to help address these behaviors and focuses solely on eating and weight concerns.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT): With its main focus on developing coping skills, emotional regulation, and strengthening interpersonal relationships, DBT can be used to treat eating disorders in outpatient psychotherapy. Eating disorder behaviors can often be a learned coping skill to cope with negative feelings or relationship stressors. DBT can help create new coping skills and strengthen a client’s distress tolerance with these emotions through mindfulness and emotional regulation skills.

Psychodynamic / Narrative Therapy: Through a narrative approach, clinicians center the client as the expert of their own life, this allows conversations between the client and therapist that incorporates the uniqueness of the individual. This further allows opportunities for the client to explore their own narrative and re-story the dominant narrative of their life by identifying hidden identities and values that have been clouded by the eating disorder narrative.

Similarly, psychodynamic therapy allows the client to explore the meaning of their life and the context in which their view on their body and eating changed. Psychodynamic therapy is primarily focused on understanding where and how the eating disorder was learned and revealing the vulnerability and pain points of those moments in order to heal them.

Eating Disorder Treatment Referrals

Sometimes an eating disorder can become severe enough to require a higher level of care. What this can look like depends on the symptoms and their severity. It is also important to consider the client's goals. If a client expresses a desire for more treatment or a different form of treatment that you can’t provide (i.e., meal support), helping them find the right resource can be beneficial for a positive recovery.

Eating Disorder Symptoms Have Become Too Severe

- Struggling With Compliance: **If the client continues to lose weight or struggle with behaviors (binging or restricting) it might be time to refer them out and see that they get care that can extend beyond the 60 minutes you have with them every week. Additionally, if you believe the client could benefit from other forms of support, it is worth aiding the client in contacting higher levels of care for assessment to see what level of treatment may be recommended.

- Medical Indication: Working with a medical provider who takes labs and monitors nutrition also serves as a way to monitor progress and determine if the client is suffering from medical complications from an eating disorder. Creating a team that provides comprehensive care to the patient creates a safer environment for the patient, as eating disorders can lead to severe health complications that can lead to mortality risk.

Comorbidities Make It Outside of Your Scope

Eating disorders can often times come with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. If a clinician is overwhelmed by their current client load or feeling unable to attend to the other diagnosis present, it might be in the client’s best interest to refer them to a provider who can offer support for both the eating disorder and the comorbid diagnosis. Psychiatric comorbid diagnosis isn’t the only comorbidity to consider. Bulimia nervosa and diabetes (diabulimia) is a medical comorbidity that requires careful consideration of medical complications related to the diabetes. Having experience or a supervisor with an extensive background in diabulimia is recommended for treating this specific disorder.

Conclusion

Navigating the complexities of diagnosing and treating eating disorders can be a daunting task for any clinician. However, with the right tools and support, you can provide comprehensive and effective care to your clients. Being able to recognize the signs of eating disorders paves the way for interventions that can lead to effective treatment.

ICANotes is a behavioral health software program designed to simplify your documentation process, ensuring you have more time to focus on your clients and less time worrying about paperwork. ICANotes includes comprehensive pre-configured clinical content for eating disorders and other behavioral health disorders.

To experience the benefits firsthand, we invite you to try ICANotes free for 30 days. Discover how this powerful tool can transform your practice by scheduling a demo today. Empower your practice with ICANotes and focus on what truly matters—your clients' well-being.

Book a Demo Today!

Hannah Norling, MA

About the Author

Hannah Norling, MA is a Counseling Psychology doctoral student at the University of Denver. Her clinical and research interests are eating disorders, recovery, and weight stigma. She is an adjunct professor at the University of Denver and has previously served as a psychology extern at the US Department of Veteran Affairs and a research fellow at the Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine.

Sources:

https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

https://books.google.com/books/about/Eating_Disorders.html?id=PtlYiPKAHlYC

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/eating-disorders

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anorexia-nervosa/symptoms-causes/syc-20353591

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022399902004889

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36987942/

https://www.cbte.co/what-is-cbte/a-description-of-cbt-e/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/anzf.1459

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128133736000143

https://www.eatingrecoverycenter.com/sites/default/files/file/2022-03/ed-guidance-levels-care.pdf

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22658-diabulimia