Eating Disorder Treatment Plan and Note-Writing Tips

Creating an effective eating disorder treatment plan is crucial as eating disorders are complex conditions to treat and manage, with therapists playing a pivotal role in helping individuals identify and overcome them. Eating disorder treatment requires a multifaceted approach and paying close attention to symptoms. With a thorough understanding of the signs and symptoms of eating disorders, therapists can build stronger notes and treatment plans to provide patients with the best chance at success. These notes and plans can also help you run your practice more efficiently and stay compliant.

In this therapist guide for eating disorders, we'll cover tips for identifying, documenting and treating eating disorders, as well as provide example eating disorder treatment plan goals and objectives.

Identifying and Recognizing Symptoms of Eating Disorders

Eating disorders impact almost a tenth of the population worldwide but are especially prevalent among certain groups, including young girls and athletes. Despite their prevalence, eating disorders are often tricky to spot. Many patients don't know the severity of the disorder or may hesitate to pursue treatment, and the symptoms can be subtle. Because of this, clinicians must watch closely for signs, symptoms and red flags.

While common in young girls and athletes, anyone can experience disordered eating behaviors, and they appear in many different ways. Eating disorders can significantly affect physical health, so clinicians must know when to pursue more intensive treatment or hospitalization.

Below are some common eating disorders and tips for identifying them.

Anorexia Nervosa

A patient with anorexia nervosa may starve themselves to lose or maintain weight lower than is normal for their height and age. The disorder's subtypes include the restricting type — which involves weight loss activities like dieting, fasting and excessively exercising — and the binge-eating/purging type, characterized by binging and purging behaviors such as vomiting or misusing laxatives and enemas.

This condition is severe and has the second-highest mortality rate of any psychiatric diagnosis, making early detection critical. Effects of anorexia can include suicide, starvation and complications from binging and purging activities. Patients with anorexia nervosa may have a strong fear of gaining weight and self-evaluation that is heavily influenced by body shape or weight.

The following symptoms may emerge as a result of anorexia nervosa:

- Low weight or weight fluctuations

- Amennorhea, or a lack of menstrual periods

- Dizziness and fainting due to dehydration

- Weakness and fatigue

- Cold intolerance

- Brittle hair and nails

- Constipation, bloating and early satiety

- Stress fractures due to low bone mineral density or osteoporosis

When assessing for anorexia nervosa, clinicians should ask plenty of questions related to the above symptoms and pay special attention to concerns expressed by family members. Clinicians should also inquire about the patient's eating habits, attitude toward body image, menstrual history, weight loss patterns and exercise habits.

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by eating high amounts of food in a short period of time, typically with the patient feeling a loss of control over their eating. When not binging, they may restrict themselves heavily to low-calorie foods. Binges are often secretive and come with feelings of shame or embarrassment. The patient usually follows binging with compensatory behaviors, such as vomiting, fasting, using laxatives or compulsively exercising to avoid gaining weight.

People of any weight can have bulimia nervosa, but those who are significantly underweight are more likely to have the binge-eating/purging type of anorexia nervosa. Like anorexia nervosa, the patient's self-evaluation is unjustifiably influenced by their body shape and weight.

Some physical signs of bulimia might include:

- Chronic sore throat.

- Dental problems due to the erosion of tooth enamel from vomiting.

- Heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux.

- Misuse of laxatives, diet pills or diuretics.

- Dizziness and fainting.

Bulimia nervosa can be harder to detect than anorexia nervosa. You may need to ask specific questions about the patient's eating habits. Screening tools can be helpful, as well as interviews with family members.

Other Eating Disorders

Other eating disorders to watch for include:

- Binge-eating disorder: Binge-eating disorder also involves losing control over eating habits and consuming large amounts of food. Unlike bulimia nervosa, it doesn't include purging, fasting or excessive exercise, and patients are often obese or overweight.

- Other specified feeding and eating disorders: This diagnosis refers to disturbances of eating behavior that may not fit neatly under the previous two disorders. For example, a patient who exhibits symptoms of anorexia nervosa but does not meet the weight criteria might have this diagnosis.

- Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID): In ARFID, patients restrict the amount or type of food eaten but do not have concerns over weight or body image. They may avoid foods to an extreme level based on sensory characteristics, such as texture or smell. They may also feel anxiety over the consequences of eating. For example, they may avoid foods due to fear of choking, vomiting or experiencing an allergic reaction. Patients with ARFID may lose weight, become nutrient deficient or become dependent on nutritional supplements.

Download our free checklist for identifying eating disorders

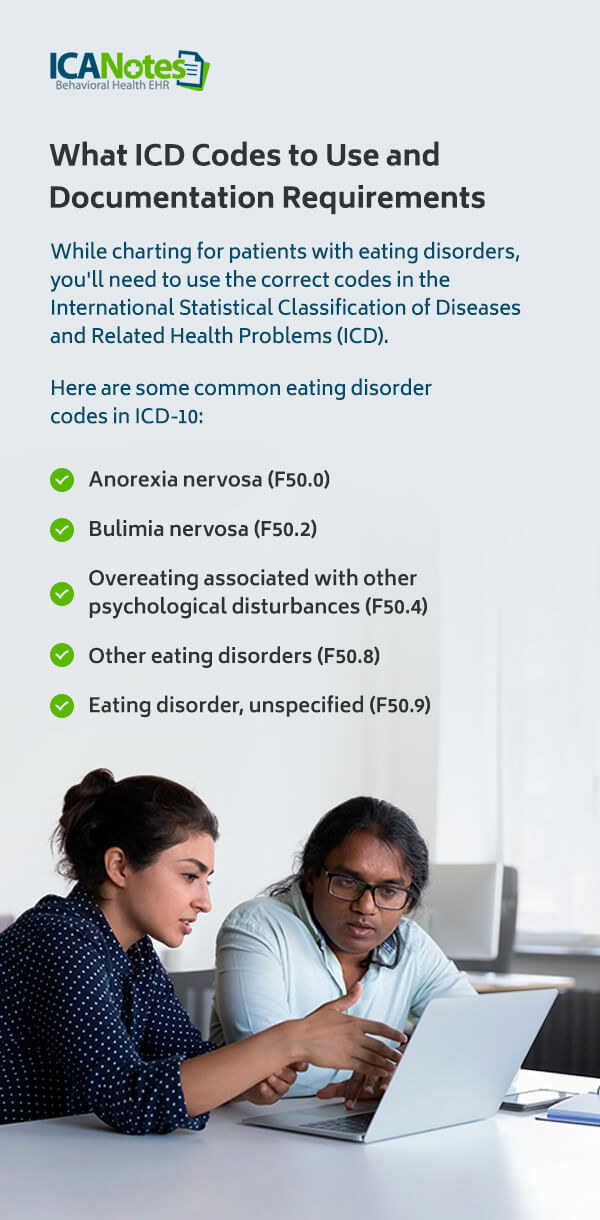

What ICD Codes to Use and Documentation Requirements

While charting for patients with eating disorders, you'll need to use the correct codes in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). Here are some common eating disorder codes in ICD-10:

- Anorexia nervosa (F50.0)

- Bulimia nervosa (F50.2)

- Overeating associated with other psychological disturbances (F50.4)

- Other eating disorders (F50.8)

- Eating disorder, unspecified (F50.9)

The next update to this system, ICD-11, will include more specificity and add more disorders, like ARFID and binge-eating disorder. It will also remove some limiting diagnostic criteria, such as requiring that binge eating occur once a week for three months.

Depending on the disorder, insurance companies may need documentation to support the diagnosis, such as the patient's body mass index (BMI), relevant blood tests and assessment scores. Clinicians may also find it helpful to retain documentation from other providers, such as updates from a dietitian or primary care doctor.

Download an Eating Disorder Treatment Plan Example

Eating Disorder Treatment Plan Goals and Objectives

With a clear diagnosis determined, you can start developing eating disorder treatment plan goals and objectives tailored to your clients' needs. Eating disorders can take many forms. Whatever your sessions look like, your therapy goals for eating disorder clients should be clear and attainable. Work with your clients to develop realistic goals that feel meaningful to them. Some example goals you might set for patients with eating disorders include:

- Client will respond to overwhelming feelings with coping mechanisms unrelated to food, such as talking to a loved one or keeping busy with a book.

- Client will reduce feelings of shame associated with eating.

- Client will become comfortable eating in social situations, such as with friends or alone in public.

- Client will improve their relationship with food and expand their approach to "healthy eating" to include some indulgent foods.

To reach these goals, you can turn to your objectives. Objectives are more concrete tasks and activities that can help your client achieve their goals and progress along their treatment plan. Here are some sample eating disorder treatment plan objectives:

- Client will keep a journal about their feelings during binging/purging sessions.

- Client will learn more about the adverse health effects of purging activities through provided worksheets.

- Client will create a list of "safe" meals they can turn to that are satiating and healthy.

- Client will visit their dietitian weekly and take notes at each session.

- Client will use self-esteem worksheets to help build a positive self-image.

- Client will eat in a public setting once a week on their own.

Tips for Writing Your Eating Disorder Treatment Plans and Progress Notes

1. Involve the Family System

Like many behavioral health problems, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and individual sessions are often beneficial therapy techniques for eating disorders. Still, many eating disorders stem from or are exacerbated by family environments that may reinforce unhealthy eating behaviors or invoke emotional responses. For example, a child with anorexia nervosa may have a parent constantly dieting or commenting on how their child shouldn't gain weight. A client with ARFID could have a spouse that wants them to "get over it."

In such situations, family therapy can help you and the client discuss their disorder with their family members. You might stress the severity of the disorder and discuss ways that the family can be more supportive of their loved one. They could start to remove harmful phrases from their vocabulary, help create healthy meals or check in with the client more often to provide accountability.

Even if family therapy isn't possible, ensure the client understands their home environment's impact. Provide tools for helping them stay resilient in less-supportive spaces or talk to their family members themselves about being supportive. Activities like these can help the client and their family build stronger connections. Many families are happy to help, but they need your guidance to get there.

2. Provide Specific Guidance

Eating disorders often come from a place of externalization. Clients might build their perceptions of "healthy" and "normal" based on those around them, like parents or even media portrayals. They may seek acceptance and validation from others rather than themselves. With this externalized approach, clients might not have a good idea of what overcoming their disorder would look like.

Try to take an active role during eating disorder treatment by providing clear guidance — often called psychoeducation — and helping the client broaden their views. Focus on shifting ideas of external approval into internalized ideas that stand independently, regardless of what others do. This approach may be particularly useful for adolescents, who tend to be heavily influenced by others' experiences.

Activity-based therapy sessions can be beneficial in helping the client build stronger internal views of the world with the therapist's gentle influence.

3. Be Explicit

Similarly, many clients with eating disorders struggle to see what constitutes unhealthy behavior. Work with the client to make unhealthy behaviors explicit. You might create a list with the client of these behaviors, such as purging or limiting calories due to a fear of gaining weight. Provide examples of healthier alternatives and thinking patterns the client can work toward.

For example, instead of thinking, "This must look like a lot of food to anyone watching," you might ask your client to focus on how good the food looks or how much fun they're having with friends. Another approach might be to provide examples of healthy, well-rounded meals the client can incorporate into their diet.

4. Include Information From Other Professionals and Treatments

If your client's treatment involves input from other adults, such as dietitians or athletic coaches, include these comments and updates in your notes. Even if you do not have direct access to other providers' information, you can ask your client about their progress with them and update your notes accordingly. You'll also want to check in on progress with other treatment approaches, like group therapy or medication.

5. Use Regular Eating Disorder Assessments

Include the results of eating disorder assessments in your notes. Some are designed for diagnosis, while others can help you keep tabs on the disorder during treatment and monitor progress. Some popular assessments include:

- The SCOFF Questionnaire: This screening questionnaire includes five questions about self-control, body image, weight loss and the role food plays in someone's life. It has a simple scoring system of one point for "yes" and zero points for "no," and two points or more suggest an eating disorder.

- Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire - Short (EDE-QS): Another screener, this short questionnaire has 12 scaled questions, with higher scores corresponding to more severe symptoms.

- Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): As the longer version of EDE-QS, this assessment includes 24 items to assess behaviors associated with eating disorders. It includes four subscales regarding restraint, eating concern, shape concern and weight concern.

- Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26): EAT-26 has 26 questions about attitudes, feelings, beliefs and behaviors toward eating. It can be a useful assessment for ongoing treatment. It's a widely used assessment that can also serve as a screening tool.

6. Simplify Your Eating Disorder Note-Writing System

As with most behavioral health conditions, writing fast, effective notes is crucial for running your practice well. It gives you more time to focus on your clients, maximize reimbursements and provide the best care possible. If you spend a lot of time on notes, consider upgrading to a purpose-built tool for the behavioral health field.

ICANotes offers a range of resources for behavioral health clinicians and clients with eating disorders. Our notes system is primarily click-based, so you can keep your hands off the keyboard and create valuable, context-driven notes in just a few minutes. It connects with the ICANotes electronic health record (EHR), so you can quickly review and add details from the patient file, like previous assessment results.

Support Your Eating Disorder Clients with ICANotes

Treatment for eating disorders is often complex, but you can set your clients up for success with effective goals, diagnoses and charting. ICANotes is an EHR designed for behavioral health professionals and packed with tools to support your clients and your practice. Our easy-to-use and low-typing charting interface allows you to create detailed treatment and progress notes for all types of therapy, including group and family therapy, without adding time to your day or interrupting your sessions.

From a fully compliant system to built-in assessments and practice management resources, ICANotes offers a robust backdrop for effective eating disorder treatment. Learn more about ICANotes online, or reach out today to request a live demo!

Start Your Free Trial Today